Gene mutations detected in blood may predict risk of one of the most common forms of adult leukemia a decade before patients are diagnosed with the disease, according to a new study by Weill Cornell Medicine and NewYork-Presbyterian investigators.

The paper, published July 9 in Nature Medicine, is the first to describe a genomic pre-malignant phase of the cancer, called acute myeloid leukemia (AML)—a disease in which the bone marrow makes abnormal white blood cells. People typically develop AML suddenly. The few known risk factors include a bone marrow failure disorder called myelodysplastic syndrome, which causes low blood counts; chemotherapy; radiotherapy; and rare inherited genes.

The research identifies acquired mutations in eight high-risk genes, some of which are associated with as much as 30- to 50-fold greater risk of developing the disease. The multidisciplinary research could aid investigators in developing new targeted therapies and interventional strategies in advance of disease diagnosis.

“We assumed that AML requires an interplay of mutations that take place before the disease manifests itself, but to find that the genetic processes could potentially start a decade earlier with the potential for prevention is remarkable. This has never been attempted in AML,” said co-first author Dr. Pinkal Desai, an assistant professor of medicine and a member of the Sandra and Edward Meyer Cancer Center at Weill Cornell Medicine, and an oncologist at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center.

For their research, Dr. Desai and colleagues at Weill Cornell Medicine—including co-first author Dr. Nuria Mencia-Trinchant, a postdoctoral associate in medicine, and co-senior authors Dr. Gail Roboz, a professor of medicine, and Dr. Duane Hassane, an assistant professor of computational biomedicine in medicine—evaluated blood samples from the Women’s Health Initiative, a large, multi-center clinical study by the National Institutes of Health that began in 1991.

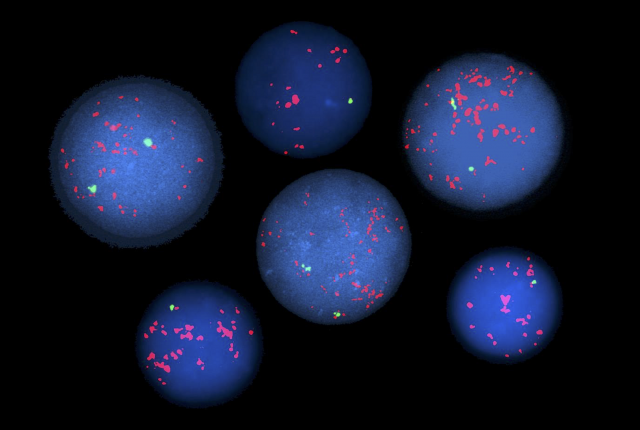

Using sensitive gene sequencing technology, the investigators looked for trace levels of mutations in genes associated with leukemia in blood from nearly 200 women who later developed the disease. They then compared the results with approximately 200 women in a control group who remained healthy.

“Our findings provide an unprecedented opportunity to start thinking about ways to intercept AML to delay or prevent it before it develops in patients at risk,” said Dr. Roboz, who is also director of the Leukemia Program at Weill Cornell Medicine and NewYork-Presbyterian and a member of the Meyer Cancer Center.

Overall, the study found that 69 percent of women in the AML group had mutations in one or more of the genes examined, whereas only 31 percent in the control group had mutations associated with the disease. Participants in the AML group who had a mutation in one of eight genes—IDH1/2, TP53, DNMT3A, TET2, SRSF2, SF3B1 and U2AF1—were significantly more likely to develop AML compared to the control group. The researchers also discovered that different mutation patterns were associated with varying levels of risk for developing AML and for when the disease emerged.

“Acquired mutations in blood, termed ‘clonal hematopoiesis,’ are a relatively common finding seen with normal aging,” said Dr. Hassane, who is also director of leukemia genomics at the Caryl and Israel Englander Institute for Precision Medicine and a member of the Meyer Cancer Center. “Our study better distinguishes these from the mutation patterns leading to AML and thus may help physicians to better select candidates for long-term monitoring.” Among the findings, the team discovered that a mutation within the IDH2 gene was more highly associated with AML, and that mutations within DNMT3A and TET2 were less associated with the disease if not accompanied by additional mutations.

The investigators’ findings pave the way for new research to monitor at-risk patients and potentially test targeted treatments that may one day prevent or delay the disease, including drugs that target mutations in IDH1 or IDH2. Other targeted drugs are in development for the mutations the team found.

“We discovered a window of opportunity preceding an otherwise acute disease, during which interventions may be considered. This finding is the result of true synergy between collaborating physicians and scientists,” Dr. Hassane said.

This research would not have been possible without the support of patients and their families, the investigators said. “We’re grateful that people are incredibly motivated to participate in our research by volunteering their samples or supporting us monetarily,” Dr. Roboz said, “not only for their own benefit but also for the population-at-large.”