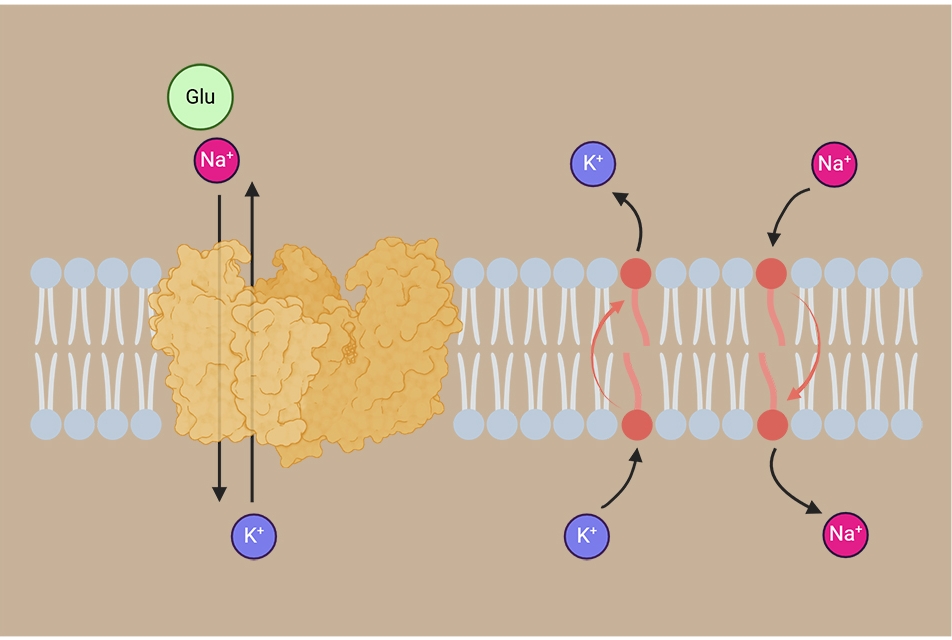

Glutamate transporters pump glutamate from the synaptic cleft back into brain cells after its release during neurotransmission. A new study by Weill Cornell Medicine investigators has found that free fatty acids, including an omega-3 fatty acid called DHA, can reduce the amount of glutamate uptake by diminishing the sodium ion gradient that powers the transporters.

The study, published Dec. 6 in the Journal of Biological Chemistry and selected as an Editor’s Pick, reveals an unexpected mechanism for regulation of glutamate transporters, which are essential for brain health. Having too much glutamate in the synaptic cleft can kill neurons and contribute to conditions like Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases. The study also suggests that fatty acids can broadly influence the function of other proteins in the cell membrane.

Dr. Olga Boudker

“The fact that these polyunsaturated fatty acids can dissipate sodium ion gradients has important implications not just for the glutamate transporters, but also other proteins which rely on ion gradients to function,” said senior author Dr. Olga Boudker, acting chair of physiology and biophysics at Weill Cornell Medicine. “If there are sites in the cells where these fatty acids accumulate in large quantities, that can significantly impact how all nearby ion channels and ion-coupled transporters work.”

Previous studies on how fatty acids affect glutamate levels in the brain—particularly whether fatty acids may directly interact with glutamate transporters—have had confusing and contradictory results. Lead author Dr. Xiaoyu Wang, instructor in physiology and biophysics at Weill Cornell Medicine, explained that these studies used tissue samples from the brain or complex cell-based systems in which many factors could skew the results.

Dr. Xiaoyu Wang

To avoid these pitfalls, the team isolated a model glutamate transporter protein and inserted it in artificial membranes so they could more clearly observe its behavior in isolation. In this simple system, they used a state-of-the-art, single-molecule imaging technique and found that the fatty acids stopped glutamate transporters from working. Surprisingly, these nanoscale machines stayed dynamic in the presence of fatty acids, arguing against the possibility that fatty acids acted on them directly. Instead, the fatty acids equalized ion concentrations across the membrane, stalling the ability of the transporter to concentrate glutamate as the pumps were left without power.

“We turned every stone to identify this mechanism,” Dr. Wang said.

While the discovery doesn’t yet have direct clinical implications, it is significant for other researchers studying the effects of fatty acids on membrane ion channels and transporters. The investigators urged scientists to consider the potential “ionophore” effect of fatty acids on sodium and potassium gradients in their experiment setup and interpretation of results.

“Since the fatty acids are signaling messengers that can trigger a chain of events affecting many cellular functions, they are heavily studied by researchers,” Dr. Wang said. “So, our findings that fatty acids have the ionophore effect should be considered as a potential mechanism of action.”

The team is currently aiming to identify other regulators of glutamate transporters beyond fatty acids, such as interaction partners and the cellular lipid environment.

The work reported in this story was funded by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, part of the National Institutes of Health, through grants NS085318 and NS134865.