Cognitive impairment is common and persistent in both adults and children with severe brain injury. Cognitive function, which refers to abilities such as hearing, understanding, and attention, can be recovered separately from motor function. However, how it is measured is inextricably tied to the display of motor function (e.g., nod or give me a thumbs up if you hear me). As a result, many people remain diagnosed as being in a less recovered state than their reality, creating profound implications on life/death decisions, treatment options, and communication efforts. While researchers have worked to improve diagnosis accuracy for adult patients through advanced neuroimaging, very little is known about covert cognition in pediatric medicine. To change this status quo, Weill Cornell Medicine investigators are publishing two papers in partnership with the National Center for Adaptive Neurotechnologies at the Stratton VA Medical Center in Albany, NY, and Blythedale Children’s Hospital in Valhalla, NY.

One study, published in Neurology Clinical Practice, shows the value of EEG markers for measuring cognitive function, without the reliance on motor function. “All conventional tests of cognitive ability have the problem that they depend on the patient’s ability to move, which may be impaired independently of their cognition. This is why we choose to measure electrical brain activity directly. We studied 43 children at Blythedale and showed that a bedside test lasting 20 minutes can be used to objectively measure and track the recovery of passive and active cognitive activity,” explained senior author Dr. Sudhin A. Shah, assistant professor of neuroscience in radiology.

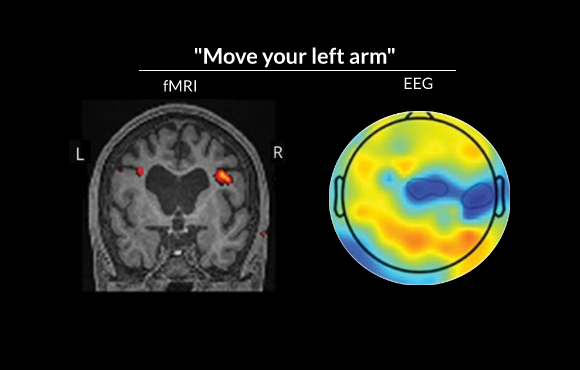

Neuroimaging results from two adolescent participants demonstrated that they could consistently activate the expected brain regions on command, despite not being able to move or communicate. Before these measurements were made, clinicians had concluded that they could not process what people say to them or perform any cognitive task

Co-lead investigator Dr. Jeremy Hill, now a senior research scientist at the Stratton VA, said, “These EEG phenomena are well-studied, but this is the first time they have been shown to produce such a clear and reliable picture at the level of the individual patient.” Most strikingly, the study identified three children whose cognitive function was more sophisticated than clinicians had been able to diagnose—a phenomenon known as cognitive-motor dissociation.

“This is an important study that demonstrates the potential of EEG markers to differentiate among states of consciousness in children,” stated Dr. Beth Slomine, co-director of the Center for Brain Injury Recovery at the Kennedy Krieger Institute. “Additionally, this is the first study that I am aware of that clearly demonstrates evidence of cognitive-motor dissociation or covert consciousness in children.”

In a companion study published earlier this year in Neurology Clinical Practice, the investigators explored multiple facets of cognitive function in two of the children who had shown evidence of cognitive-motor dissociation. They developed a hierarchical, multimodal toolset using fMRI, PET and EEG for individualized assessment. “We took multiple complementary approaches to assessing cognitive function, to show the breadth of their auditory, linguistic and selective attention abilities,” said Dr. Shah, who is also an assistant professor of neuroscience at the Feil Family Brain and Mind Research Institute. “For the five-plus years since their injury, nobody had recognized that these children could hear, understand and follow instructions, because they could not show any outward signs of doing so,” added Dr. Hill.

Together, these publications provide landmark evidence that neuroimaging and neurophysiological methods can address the significant clinical problems presented by severe brain injury in the pediatric population, a field that is currently about 30 years behind similar work in adults. As findings continue to emerge, they will be instrumental in shaping the guidance for how new and chronic patients are assessed and ultimately improve the standard of care.

According to Dr. Shah, there are still substantial issues that remain to be dealt with. Recognizing a child is aware, but unable to communicate, is a very important milestone, but it is only the first step. Clinicians still cannot establish two-way communication with these children—a problem that has not been solved in adult patients either. “By showing that this can be done feasibly in children, and by identifying children who are isolated, we hope the research and clinical communities will begin to recognize the problem and work on solutions to accurately diagnose and, eventually, treat.”