An iron-regulating molecule called hepcidin is produced by the immune system and restricts the growth of gut bacteria after an intestinal injury, helping to heal the lining of the intestine, according to a study by Weill Cornell Medicine, NewYork-Presbyterian and Institut Cochin investigators.

The study, published April 10 in Science, was conducted in mice and human samples and could have important implications for treating gastrointestinal diseases that damage the lining of the intestines as a result of infection, chronic inflammation or cancer. Currently, most treatments for gut-damaging conditions like inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) focus solely on reducing inflammation and do not directly address the need to promote tissue repair.

“Not being able to heal your intestine is a major problem in patients with inflammatory bowel disease and other gastrointestinal disorders,” said senior author Dr. Gregory F. Sonnenberg, associate professor of microbiology and immunology in medicine in the Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology and a member of the Jill Roberts Institute for Research in Inflammatory Bowel Disease at Weill Cornell Medicine. “There is an urgent need to better understand the pathways that promote mucosal healing and harness that knowledge to design new treatment strategies.”

Dr. Gregory F. Sonnenberg

Bleeding in the intestines is often one the first signs of diseases like IBD or colorectal cancer, said lead author Dr. Nicholas Bessman, a postdoctoral associate in medicine at Weill Cornell Medicine. Intestinal bleeding may further exacerbate these diseases or hamper healing by fueling overgrowth of gut bacteria. This happens because blood contains large amounts of iron, which is essential for bacterial growth. To investigate the potential role of the iron-regulator hepcidin, the team collaborated with Dr. Carole Peyssonnaux and other researchers at the Université de Paris, INSERM, Institut Cochin, and examined intestinal healing in mice with and without the hepcidin gene.

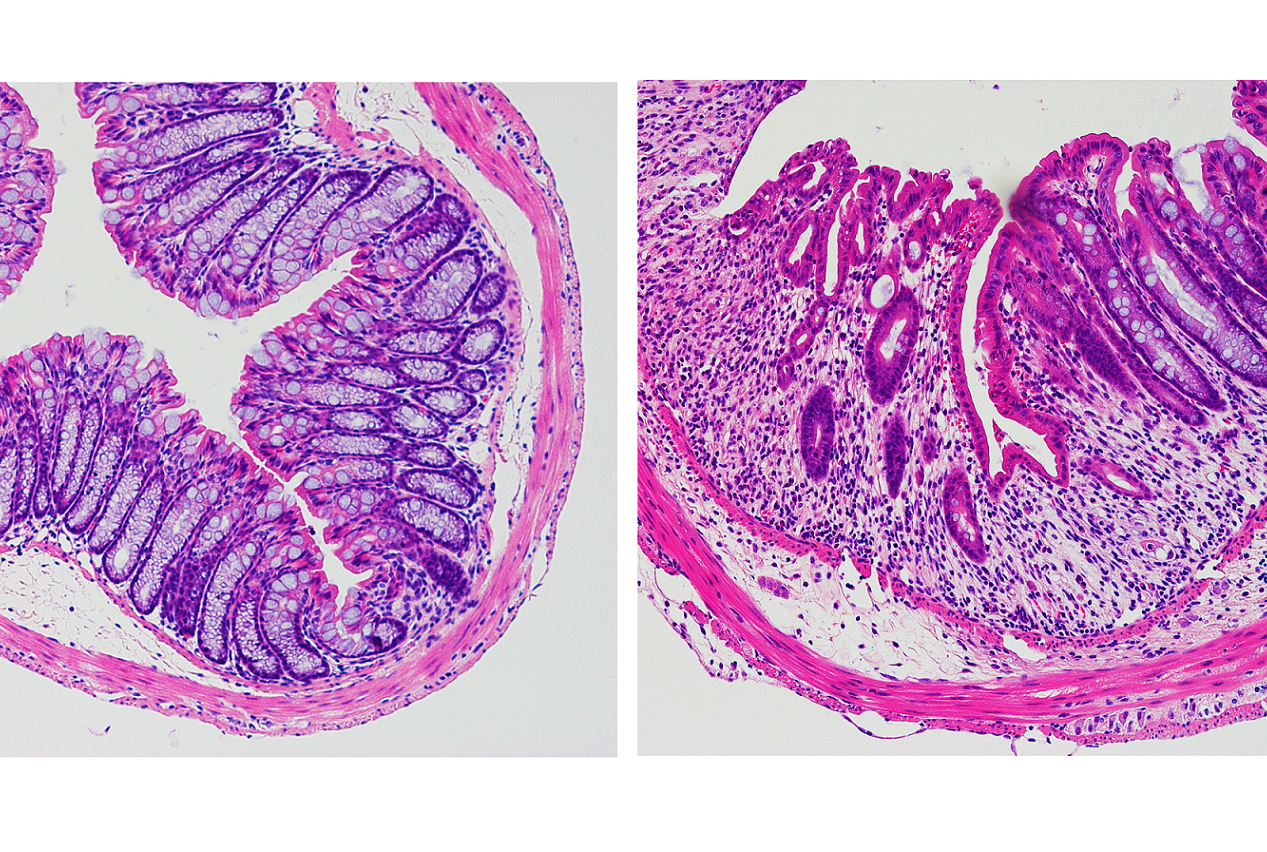

“We found using mouse models that hepcidin is critical for healing in the intestine,” Dr. Bessman said. When the team looked closely at gut tissue from mice, they were surprised to discover that hepcidin is produced by dendritic cells, which are a critical part of the immune system. Normally, hepcidin is primarily produced by the liver, but after a gut injury, production by the liver is drastically reduced and rather the immune system starts to produce it locally in the gut," Dr. Bessman said.

Dr. Robbyn Sockolow

To determine if this also happens in humans, the team collaborated with Dr. Robbyn E. Sockolow, a professor of clinical pediatrics at Weill Cornell Medicine and director of pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition at NewYork-Presbyterian Komansky Children’s Hospital. Using samples collected from pediatric patients with IBD, they confirmed that dendritic cells in the human gut also produce hepcidin in response to injury. “It is exciting to see results obtained in mouse models translate to patient samples, which indicates that this pathway is clinically important in individuals with IBD,” Dr. Sockolow said.

Next, they conducted a series of experiments in mice and determined that hepcidin interacts with a key iron transporter in the gut called ferroportin on intestinal macrophages. It is well known that this interaction promotes ferroportin degradation and subsequent intracellular iron sequestration. In mice lacking hepcidin in dendritic cells, iron levels rose in the intestine, which fueled the growth of bacteria that rely on iron. Meanwhile, a population of a beneficial bacteria called Bifidobacteria that promotes gut healing, was drastically reduced. These collective changes to gut bacteria prevented normal mucosal healing. Critically, the team found that administering a drug called deferoxamine, which blocks bacteria from accessing iron, completely restored gut healing in the mice that lack hepcidin.

Dr. Nicholas Bessman

“We found that when you damage your gut, the immune system produces hepcidin in the intestines,” Dr. Sonnenberg said. “Hepcidin instructs immune cells called macrophages that eat red blood cells to sequester iron away from gut bacteria, and this is an essential step that allows the intestine to heal.”

The team is currently exploring whether hepcidin can be developed as a potential therapy for gut diseases. "These findings suggest that hepcidin mimetics could be beneficial to patients with a damaged intestine,” Dr. Peyssonnaux said.

“We might be able to develop methods to locally deliver hepcidin directly to the intestines to promote or enhance healing in individuals with IBD, cancer and infections,” said Dr. Sonnenberg.

The study was supported by the NIH (F32AI124517, R01AI143842, R01AI123368, R01AI145989, R21CA249274 and U01AI095608), the NIAID Mucosal Immunology Studies Team (MIST), the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation, the Searle Scholars Program, the American Asthma Foundation Scholar Award, an Investigators in the Pathogenesis of Infectious Disease Award from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund, a Wade F.B. Thompson/Cancer Research Institute (CRI) CLIP Investigator grant, the Meyer Cancer Center Collaborative Research Initiative, and Linda and Glenn Greenberg, and the Roberts Institute for Research in IBD.

This work was also supported by funding from the European Research Council under the European Community’s Seventh Framework Program (FP7/2011-2015 #261296), the “Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale” (DEQ20160334903) the Laboratory of Excellence GR-Ex, reference ANR-11-LABX-0051, and the “Investissements d’avenir” of the French National Research Agency (ANR-11-IDEX-0005-02).